- Home

- Beth W. Patterson

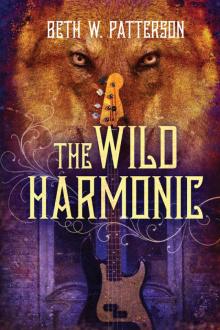

The Wild Harmonic Page 7

The Wild Harmonic Read online

Page 7

“Respect and boundaries are the keys to survival of so many different packs. We all have to get along, as we know from other bands. There’s no room in ‘the world’s biggest small town’ like New Orleans for acrimony, and when it exists, it’s rough.

“On to the howl: it’s one of the things that defines us. The way we howl together in our pack is our art, and a way to let off steam while strengthening our bond. But sending out a message is a completely different animal, pardon the expression. When wolves howl, it triggers a chain reaction, and so for us the need to automatically join in is visceral. It’s as infectious as a yawn. But because we have a scheming human nature, we must rein this in and really listen to the message that’s being conveyed.

“We can’t allow it to get out of hand. It’s fine for humans to mindlessly raise their voices at football games, but if we start howling frivolously, the meaning becomes taken less and less seriously, like …”

“The Boy who Cried Wolf!” we say in unison.

“It’s bad enough with humans,” he continues. “With the human race, collective focus can take the form of everything from prayer and chants to mass hysteria and riots.

“You know who knows the most about this stuff?” he suddenly brightens. “Abuelo.” I smile at the realization that the wise old Honduran busker and everyone’s “grandfather” figure is actually a shifter. “Come on,” says Teddy, rising from his chair and pulling me to my feet. “Let’s go pay him a visit.”

But when we arrive at his home on Saint Claude, we discover his doorstep buried under a pile of newspapers, some of which are crumbling from the elements. I don’t know him well enough to have noticed his absence, but my flesh begins to prickle. We wander the perimeter of his house, but see no signs of struggle and smell no traces of fear. It’s as if he’s simply vanished into thin air.

The neighbors all report that they too have seen no sign of this kindly old catratcho. Teddy says that it’s not like him to simply up and migrate like his monarch butterfly form.

Sometime during the night I awaken to find myself inside my apartment, standing at my front door, and locking all three locks compulsively, over and over again. The button on the doorknob, chain latch, and deadbolt go through a ritual before I realize that my anxiety is causing me to sleepwalk. Ripping off my clothes, I flow into the beast of me and sleep with one eye open, ears always attuned like satellite dishes.

Tonight my role is the Enhancer. I’m playing with the Round Pegs at Big Mama’s Lounge, the box office lounge of the House of Blues. We’re celebrating an EP release. It’s a satisfying job for me: I’m on the record, I had made some good money for the session work, and got a little credit for my bio without the responsibility of being a bandleader. So it’s a nice little ego trip when they gobble up CDs and ask me to sign them.

I am, of course, dolled up for the show in an informal but graceful tunic over black leggings and short boots with soles soft enough for me to feel the vibrations through the floor. Not exactly rock star, just enough effort to look like I give a shit about my image. I am painted and scented as befitting a gal who is going to be watched under bright lights by many. I’ve even remembered to run a brush through my long hair. I step back, tap into my pack mentality, and feel the connected energies of everyone.

The horn players are a tribe unto themselves. Some have played together on assorted gigs for years, and at least one is a newcomer. But history doesn’t seem to matter. One minute they are clustered in a black-jacketed cackling bunch, good-naturedly ragging on each other and blowing scattershot notes. Then Salty the drummer gives a countoff and they jump in together as a single entity: dynamics, chords, tasteful rhythms that lend themselves to each song, as if they had practiced this music for years. I grin. It’s very similar to how the drummer and I lock into each other, enhancing each other’s ideas, even occasionally trying to crack each other up.

The breaks are short but jovial. Tonight we are a ten-piece lineup, and many of us haven’t seen each other in a while. Some folks do shots, some sip on beers, the cloud of smoke thickens, and I get drawn into the assorted clusters to catch up on gossip and exchange the sickest jokes possible. John the guitarist and I try to out-shock each other before it’s time to hit the stage for a second set.

As I settle back into position and we wait for everyone else to reassemble onstage, Salty beckons to me from behind his kit. I lean in and he hisses, “Guess what I bought the other day? An authentic 1978 Battlestar Galactica Colonial Viper!”

My hand instinctively grabs his shoulder hard. He knows my obsession with these collectibles. “No way!” I bark. “I remember those! They took them off the market after a kid shot a pellet down his own throat! A deadly toy that I don’t have! Where the hell did you find it? I’ve wanted one forever!”

His feral grin drives me nuts. “A garage sale,” he brags. “The little spacecraft was still in its original box.” If I didn’t love Salty so much, I could choke him. But now the break is over and it’s time to get back to work.

Tony Fox, one of our trumpet players, is still out wandering around somewhere. Some musicians are notoriously flaky, but it’s not like the clever red-haired man to be this unprofessional, and we’re irritated. Finally P.H. Fred the bandleader calls a song, Salty counts us off, and it’s back to the show.

We engage the crowd, we try to unseat each other, we laugh at ourselves, and we alternate between intense virtuosity and goofy histrionics. I suspect that some of these players might also be shifters of some sort, but we are all one hundred percent musician.

By now anything goes. We seldom stick to the set list, and just go with the flow. P.H. Fred is on a roll. We ease into a vamp and he dives headlong into a shocking monologue that has the audience alternately laughing and gasping. The crowd is digging the spontaneous absurdity. Somehow a cheesy mashup of Bon Jovi and Styx is born under the spontaneous title “You Give Blue Collar Man a Bad Name.” A few times the bari sax player and I find creative and amusing ways to flip each other off. By the time the gig is over everyone is hugging. A few musicians swap numbers with the hopes of more gigs together in other settings. These “warm fuzzy” nights are rare, so I stand back and just savor the energy.

As we pack up our gear after the gig, Salty ceremoniously presents me with a box wrapped in a plastic Rouse’s shopping bag. I don’t even have to ask what it contains, and I throw my arms around his neck, positively giddy.

“How much do you want for it?” is my next question.

He bats his hand at the air. “The lady selling her stuff didn’t even know what a collector’s item she had, and charged me all of five bucks for it. Come sing one of your Cajun French songs on my Big Easy Playboys record and we’ll call it even.” I love Salty’s Cajun hybrid project, so it’s a win-win deal for me. Clutching my new treasure to my chest, I make my way to the bar for one last celebratory beer, insisting on buying one for Salty too.

My elation is short-lived, though. Tony is still missing, his prized trumpet still on its stand onstage. I don’t know him as well as I know the others, but I’m concerned all the same. Half the band members are on their cellphones trying to get word from the police or hospitals. Ian, another horn player, gathers Tony’s things and says that he’ll keep them safe. Someone else volunteers to swing by his house and check up on him.

I don’t want anyone to see me constantly looking over my shoulder as I load up my car, so I let my nose and ears rule my senses. There are no unusual sounds or scents, but a drunk man weaving past me pauses and calls out, “Out here by yourself? You need to find yourself a guardian angel, baby!” Every nerve suddenly screams a warning bell, and a low growl resonates in my collarbones. I manage to control myself until I am safely in my apartment, and the beast comes out. Anger is safer to process in animal form, for human rage is far more deadly.

No! I say in my mind to this invisible threat. This is my territory. Leave our musicians alone.

Raúl and I go to the New Orleans Athletic C

lub, which blows my mind once we enter. The colossal old building—old for an American establishment, anyway—established in 1872, is a tribute to a nearly obsolete sort of reverence for the betterment of human physique, before the age of refined sugar, processed foods, and the equally deadly unrealistic body image.

This place is like an ancient temple with modern trappings. Huge columns with ornate molding support the rooms that are softly lit by delicate lamps hanging on chains. No amount of space is wasted, yet there is enough room here to prevent claustrophobia. Rows of myriad workout machines sit opposite a small pub serving everything from wine, martinis, and beer to smoothies and protein shakes, all on the first floor. The second has a huge ballroom that looks better suited for a lovely old dancehall, but is dedicated to classes: yoga, boot camp, body shaping, cardio kickboxing, and others. Still, the floor-to-ceiling Palladian windows and gilt-framed mirrors make me wonder what I’m doing here. Across the hall there are more machines for spinning classes, some basketball hoops, and a pool on the other side of the building. The third floor has a track that runs around the perimeter of the court. Even the rooftops are used for running.

He talks me through some of the weights, and then sends me to the class called Boot Camp held upstairs in the ballroom.

Boot Camp is a rude awakening. I consider myself to be in fairly good shape, but realize that too many of my muscles have been long-neglected from too much playing and little else in lieu of physical activity. We go through a rapidly paced alternation between running laps, planking, weights, push-ups, squats, and stairs. Still I am able to keep up with the rest of the class. The only person who betters me is an exotic-looking woman; tall and raven haired, sporting a single blue glass eye around her neck that is striking against her golden skin. I hazard a guess that she is a model and has to maintain her figure through training every day. She barely appears winded. Her only sign of effort is a heart-shaped patch of sweat on the small of her back.

By the time I meet Raúl on the landing halfway down the stairs, I am trembling from exertion. “How did it go?” he asks, knowing full well what I am going to say.

“I hate you,” I snarl. He laughs, throwing a towel over my face.

We sit for a spell in the bar. “Raúl, this gym must be a playground for you. Lots of fit women for you to ogle, all the heavy machinery you could ever want. I’m sure they have stuff like this back in Mozambique, but is it the combination of absurdities that keeps you here in New Orleans?”

Raúl’s normally cheery face becomes grim. “I can never go back to Mozambique. I have no passport.”

“Then how did you get …?” I venture, then snap my jaw shut. He’s never opened up to me about his past before, and I know better than to push the issue.

He quickly changes the subject by humming a mantra. “Did you know that mantras are much more powerful for lycans? Try this, Little One. Wahe Guru or Waheguru is a Sikh mantra that means ‘Wonderful Teacher’ but it can also mean ‘the Divine.’ Not only is it a direct pathway to bliss but it is also a word you can still utter when you are in full wolf form.” He brings to mind those viral videos of talking husky dogs, and I am grateful for this tiny bit of knowledge.

I sing Waheguru in my car all the way home, until I stumble up the front steps of my apartment. My newly-sore muscles protest, and my mantra changes to some inarticulate swearing.

Alma’s second line parade starts at The Spotted Cat. Raúl is on snare drum, and I’ve got a metal guiro that someone brought me from Brazil that makes a satisfying raspy sound with its steeltoothed scraper. I see members of Alma’s band congregating, as well as a few of the guys from Egg Yolk Jubilee. Trumpets, trombones, drums, a sousaphone, and assorted people who just want to march along all cluster as we start down Frenchmen Street with “Down By the Riverside.”

As we cross St. Claude Avenue and go deeper into the residential area, people hear us coming and run to the curb to clap along. One man I’ve never seen before stands on his porch and plays along with us on his trumpet. “This Little Light of Mine” has never given me such goosebumps before.

A lost-looking young man with boundless energy comes trotting into the fray. He seems sweet—fresh-faced and eager, a blank canvas carrying an insanely heavy-looking backpack. “What is the occasion?” he asks me.

I pick up on his accent. “Where are you from?” I ask him first.

“I’m from France,” is his breathy reply. “I am just arriving today, and I want to know what this ceremony is?”

So I switch to French; I haven’t spoken much since I moved to New Orleans from the Cajun area of St. Landry Parish at age eighteen. But it seems that this parade can be better explained in my second language, which forces me to simplify. It comes back to me in a mélange of the standard European French I learned in school and the Cajun French I grew up hearing from my friends’ parents.

I tell him, “Our friend is dead. Her funeral was yesterday, she was buried yesterday. Today we celebrate her life. She was a formidable singer, and all the world loved her. This parade commenced at the bar where she sang, and will end at her mother’s house.”

He is incredulous. “A funeral parade?” he asks in French.

“Yes. Come with us,” I command. Alma would have loved to have introduced a young foreigner to our unique customs.

And with the same zeal as those of us who knew and loved her, he dances alongside us for the remaining mile and a half. He does not lay down his heavy load until we stop, where Alma’s mother emerges from her house, crying and smiling and offering us drinks.

Stepping into Rowan’s studio, I try to keep my pulse down. My eyes adjust quickly from the blazing daylight to the soft energy-saving lighting of a building humming with electricity on a palpable grid, and his intoxicating scent seems to come in from everywhere. This is, after all, his territory. I grit my teeth and will myself into self-control.

He’s in the control room finishing up a session, tweaking a few rough bounce mixes before storing them to the hard drive and giving copies to the band. I park my butt on the couch behind him in the “sweet spot”: the point between the two speakers that gives the truest sound of the mix. My ears are captivated by his magic, yet my eyes wander and I find myself staring at the nape of his neck, which I have a wild urge to nibble. I try to rein in my desires and my gaze wanders with a will of its own to the backs of his calves revealed by his shorts. His legs appear to be surprisingly muscular and defined, especially for a guy who sits at a studio console all day. I snap my head in a sobering shake and drop my gaze to ground level, where the whiteness of his sock stands out in stark contrast to his caramel-colored ankle.

I bite back a groan. Sweet spot, indeed. I can’t look at him anymore, decide to rifle through the stack of books on the table next to me, and busy myself with flipping through a copy of Zen and the Art of Producing. The words of the pseudonymous author Mixerman are both bitingly true and amusing, and I attempt to get swept away somewhat in his sage advice.

My eyes dance across the page, but sound hits me from all directions. I hear him pad softly into the main room and gently instruct an intern: “Now, the way you need to wrap a mic cable is by alternating your loops … over and under … clockwise and counterclockwise … so that it won’t develop any kinks and it will unroll smoothly just like a lasso. See …?” I hear the thump of cable hitting the floor. He is a born instructor. I hear equipment being gathered, instrument cases closing, and the volume swell of goodbyes as musicians begin to trickle out of the studio. I know a few of these guys on the session, and we pause to make small talk as they depart.

The intern finally leaves, and it’s just Rowan and me in the control room. We’ve worked alone together in the studio before, but this is something new. Intimate. He rolls up his chair to face me on the couch, picks up his guitar, and casually noodles around with a few blazing licks. I find it an absolute crime that he does not perform live anymore. We take a moment to indulge in our unique shared humor, pulling up some v

ideos on You Tube of some exquisitely bad music. We have a good belly laugh at some songs by Shooby Taylor—arguably the world’s worst scat singer. By the time we get down to business, I am finally relaxed enough to begin my tuition.

We get comfortable in the drum room, which is a five-sided chamber. Rowan has hinted before that there are more advantages to its shape than just acoustics, but for now we have to touch on the most urgent skills.

He cuts to the chase. “Warding takes practice, but it’s the most basic and necessary measure of protection. When you’re with the whole pack, or even with one of us, we can cover you while you learn. There is a subtle energy that connects us all. While warding doesn’t make us truly invisible to the senses, we can disengage from this flow so thoroughly that we don’t even enter the thoughts of someone whose attentions we don’t want. There is a safety in removing your imprint from the energy patterns that can be seen by others. You are still one with the oscillations, for if you were to stop vibrating, you would begin to die.

“Now, about shielding. It’s different from warding in that it’s strictly on an individual level. This is what some would call ‘emotional control.’ Do not deny your feelings, only tuck them away until you are safe. I think of it as ‘freezing,’ allowing the emotions to thaw later in a secure environment. Until then, the show must go on, so to speak. Trust no one.”

He talks me through a simulated pattern, asking me to imagine situations in which I am afraid, angry, and even relaxed and off guard. Each time I am instructed to visualize a hard, clear ball protecting me, or a gossamer veil that extends to cloak my immediate surroundings. The trick is to draw on the energy that feeds both the woman and the wolf of me. I’m failing miserably at this, and decide that if I express resistance, he won’t see that it’s largely because I desperately want to prove myself worthy of him.

The Wild Harmonic

The Wild Harmonic